Moors in the European Renaissance

"Portrait of a Moorish Woman" by a student of the School of Paolo Veronese in Venice (1550)

|

Following the expulsion of many Moors (as well as other Muslims and Jews)

from the Iberian peninsula by Manuel I of Portugal in 1496 and Ferdinand V and Isabella I of Spain in 1502,

some Moors migrated to other parts of Europe. At the same time, Europeans began importing

many kidnapped slaves from the West Coast of Africa. And as it became quite

fashionable for European nobles to have African slaves, Moors were increasingly the subject of scorn in European society.

Nevertheless, Europeans had held Africans in high regard for centuries prior--from the Black Catholic patron Saint Maurice to the

black knight, Sir Morien. Therefore, despite increasing anti-Black racism, it was still possible for many Africans to move to

the highest echelons of European society. Some became nobles, intellectuals, military leaders, as well as paid musicians and other

respectable professionals in royal courts throughout Europe. They became so numerous in England that Queen Elizabeth I issued a warrant (July 1596)

and a proclamation (January 1601) by which she expelled all "Blackmoores" from England:

The Queen is highly discontented to understand the great number of Negroes and black a moors which are [in England];

who are fostered here, to the great annoyance of her own people who are unhappy at the help these people receive, as also

most of them are infidels having no understanding of Christ...

After Elizabeth's reign, however, Africans were once again present and active in England and elsewhere in Western Europe.

Alessandro de Medici, the mulatto ruler of Florence from 1530-1537

|

Royalty and Nobility

European Moors were not just servants and talented employees in royal courts, but also royals and members of the aristocracy. One of the most

famous of all was Alessandro de Medici, Duke of Penne and Duke of Florence, who was commonly called "il moro," Italian for "The Moor". In his day, he was officially recognized as

the son of the powerful Lorenzo II de Medici (1510-1537) and an unknown African woman. Alessandro was the last Medici to rule Florence, having assumed the throne

at the young age of 19. He commissioned the construction of the Fortezza da Basso, a massive fortress in the historic center of town, as well as other fortresses around town.

Purported to have had many enemies, he was assassinated by his own cousin, Lorenzino de Medici in 1537.

"Portrait of an African Man" features an unknown noble in the Austrian royal court, by Jan Mostaert

(1520-30 AD); housed in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam

|

Dutch painter Jan Mostaert (1475-1556) depicted a Moorish nobleman who was

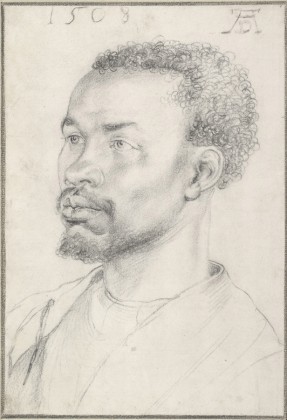

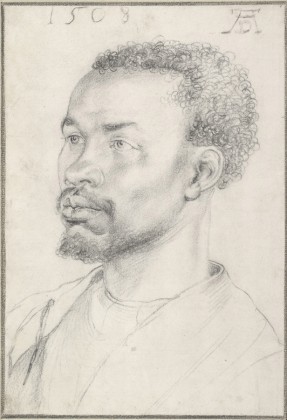

likely in the royal court of Margaret of Austria in Malines. Other Moors of high social status posed for German artist Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) in 1508 and 1521. While not much is known about

the man, the woman's name was Katherina from Antwerp, Belgium, and is depicted with typically "Moorish" clothing of high

regard (both of whom are depicted below). Other portraits of wealthy Moorish women, such as the one by a student at Paolo Veronese's school

in Venice (shown at the top of the page), depict them dressed in more European-style attire.

Durer's "Portrait of an African Woman, Katherina" (1521)

|

Albrecht Durer's "Portrait of an African Man" features an unknown noble (1508); housed in the Albertina in Vienna

|

Some Moors who had converted to Christianity in the Iberian peninsula in the 1500s also became prominent figures

in society, as shown in the painting below that depicts a busy scene in Lisbon's Alfama

harbor. The Black man mounted on a horse in the foreground

appears to be of the highest social status of anyone in the scene. The

red cross on his cape most likely represents membership in the Order of Santiago

(St. James of the Sword), an Iberian military knighthood that adopted the symbol dating back to the

12th century AD. It is indeed documented that several Africans had been admitted to the Order,

including Luis Peres (1550), D. Pedro da

Silva (1579), and Joao de Sa Panasco, who was described in a 1547 royal court document as a

"homen preto cavaleiro de minha casa" or "black man knight

from my house" (1547).

Chafariz d'el Rei in the Alfama District, Lisbon (1560-80), the Berardo Collection, Lisbon

|

Abram Petrovich Gannibal (1696-1781)

|

Several Africans who were kidnapped and later presented to royal families eventually became educated and rose to prominent positions in local

society. Such was the case of Abram Petrovich Gannibal (1696-1781), who is better known as the great-grandfather of Russian literary hero, Alexander

Pushkin. Gannibal is of uncertain origins (scholars commonly believe he was born in either Eritrea, Ethiopia, or Cameroon), but he is known to

have been kidnapped at the age of 7 by Ottoman slave traders and taken to the court of Sultan Mustafa II in 1703. He was later bought by

a Russian ambassador who sent him to the court of Emperor Pyotr Alexeyevich (Peter the Great). Peter saw greatness in Abram, who was asked to

accompany Peter in military campaigns. Like many nobles of his day, Abram studied in France in 1717, where he took up foreign language, mathematics, science and war studies.

A year later, he joined the French Army, quickly rose to captain, and proved himself worthy in battle while fighting against the Spanish. After sustaining an injury, he

enrolled in artillery school in Metz, France. He completed his education by 1722 and returned to Russia to work as a military engineer. In 1725,

following the death of Peter the Great, Prince Menshikov rose to power and exiled Abram to Siberia. However, in 1730, upon the ascent of Empress Elizabeth, the daughter of Peter,

Abram was pardoned and made major general and superintendent of Reval from 1742-1752. He later retired to an estate with hundreds of European slaves.

Angelo Soliman (1720-1796)

|

An Austrian named Angelo Soliman (1720-1796), who is said to be a native of Central Africa where he was kidnapped at a young age and later presented in 1734 to Prince Georg Christian, Furst von Lobkowitz. Soliman served as Georg's

confidant, however, as he grew older, Soliman became fluent in 6 languages, was a master swordsman,

navigator and renowned music composer. In his adult life, he climbed to the top of Vienna's high society and joined Concord Freemason's lodge where he

became Grand Master and a major intellectual influence on Austrian Emperor Joseph II, Count Franz Moritz

von Lacy, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Josef Haydn.

Gustav Badin playing chess

|

At a young age, Gustav Badin (1750-1822, named Couschi at birth), was kidnapped, taken to Sweden and presented to Queen Louisa

Ulrika of Prussia in 1757. Intrigued by the teachings of Rousseau, Louisa set out to teach Gustav how to

read and write, and about Christianity and etiquette, as an experiment to see if a "morian" (Swedish for Moor) could be "civil."

Then he was allowed to make all his own choices, unlike her other children. He later pursued poetry,

theatre and dance, and based on his extensive library of mostly French books, was well versed in the French

language. Upon the death of Queen Louisa, it was Gustav whom she trusted with her personal files, perhaps to

the dismay of her son. In his latter years, he married twice, owned two farms, and was an esteemed

member of the Freemasons as well as the Swedish secret societies of Par Bricole, Svea Orden, and Timmermansorden.

Julius Soubise on the cover of satirical book, A Mungo Macaroni

|

Julius Soubise (1754 - 1798) was kidnapped at age 10, taken to Britain by Naval Cpt. Stair Douglas and given to the Duchess of

Queensbury. Charmed by his intelligence and good looks, she sent Soubise to school where he mastered the violin,

riding and fencing. As he grew older he rose to prominence in London high society and was known for living a very lavish

lifestyle. He was even featured in William Austin's satirical works,

The Duchess of Queensbury and Soubise and

A Mungo

Macaroni. In his latter days, he left England for disputable reasons and started a riding school in Calcutta, India in 1777.

Musicians

John Blanke, trumpeting at a royal tournament circa 1510

|

As aforementioned, Moors

frequented the courts of European royalty, not merely as servants, but as skilled employees. Perhaps no other skilled workers were as highly valued to

the ruling class as musicians and entertainers. According to the UK National Archives, Scotland's King James IV (1473-1513) employed several African drummers and

choreographers in 1505. King James' Treasurer's accounts also recorded monetary payments to

several black women including, "Blak Elene" (1512), a "blak madin" , "Blak Margaret" (1513), "two blak ladies", and a

"Helenor, the blak moir [Moor]".

Similarly, England's King Henry VII and Henry VIII's courts had African employees. The most famous was

John Blanke (1500s), a musician who was paid on a daily basis,

as noted in the Treasurer of the Chamber's accounts. His image can be seen on the UK National Archives' "Westminster Tournament Scroll" of

Henry VIII (shown at right). The Archives asserts that it was perhaps one of the most important royal galas, suggesting the high regard

for John Blanke, "the blacke".

"The Engagement of St. Ursula and Prince Etherius" by Master of Saint Auta in the National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon, Portugal (c. 1520)

|

"Moor and Peasant in Dance," in the Nuremberg Municipal Library

|

A Moorish military musician in Berlin by Peter Schenk (c. 1690)

|

Gondoliers and Boatmen

Moorish gondolier in Venice c. 1495

|

Moors were employed in Renissance Italy, Portugal and elsewhere as skilled gondoliers and boaters, as thoroughly documented. For instance,

Venetian historian Marino Sanuto

(or Marin Sanudo il Giovane) remarked on Venice's Black gondoliers

Praise of

the City of Venice (1493):

"Certain boats are made pitch black and beautiful in shape; they are rowed

by Saracen negroes or other servants who know how to row them. " Sanuto also affirms that many of them were paid wages:

"The basic cost ofone of these boats is

15 ducats, but ornaments are always required, either dolphins or other things,

so that it is a great expense, costing more than a horse. The servants, if they are

not slaves, have to be paid a wage, usually one ducat with expenses, so that,

adding it all up, the cost is very high."

A gondolier's services being used during a hunting expedition c. 1490-95 at the Getty Museum (credit: Sailko)

|

Venetian artist, Vittore Carpaccio, who studied under Gentile Bellini, depicted

such Moorish gondoliers in his painting "The Healing of the Madman" (1496) shown above. Carpaccio's work, "Hunting on the Lagoon," also attests to Moors not just steering

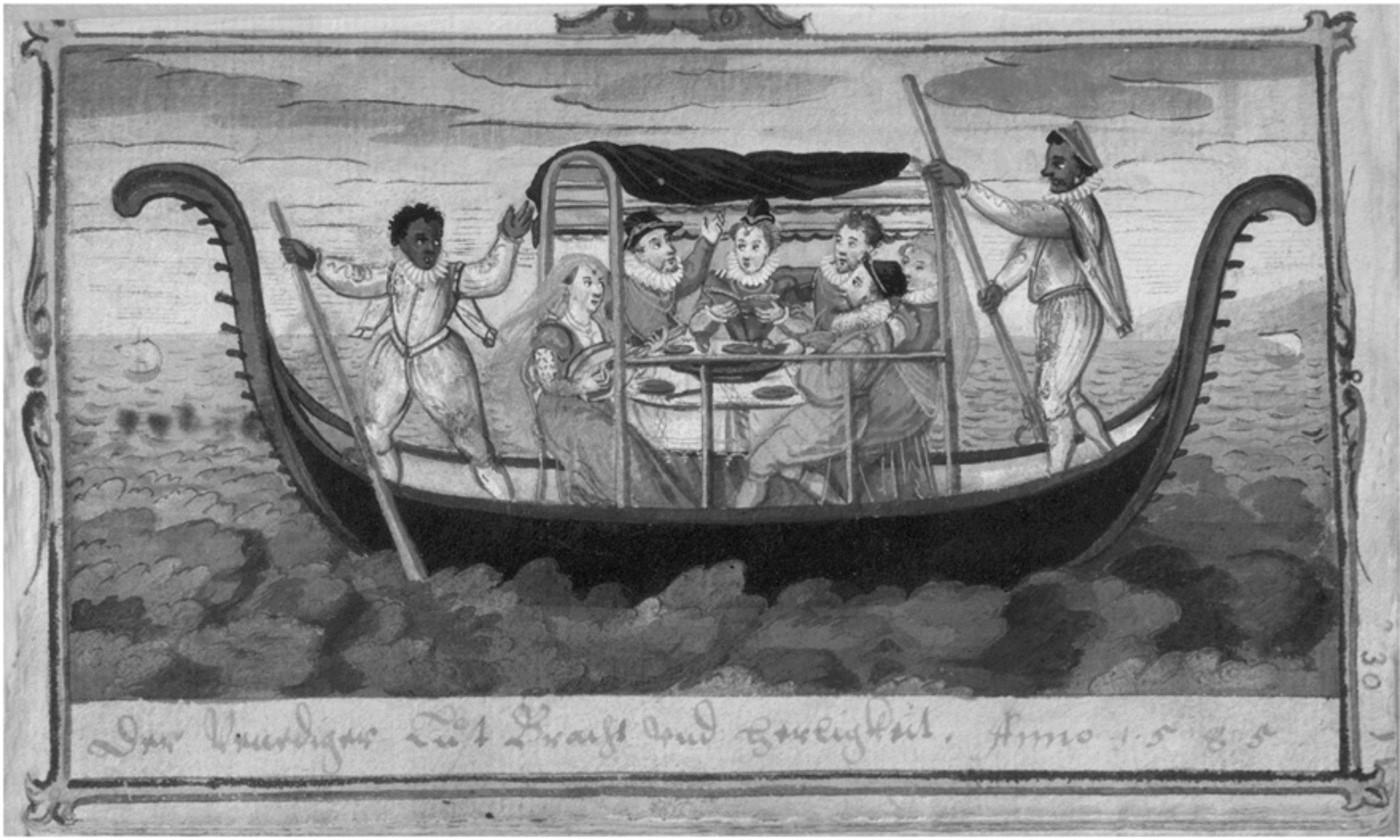

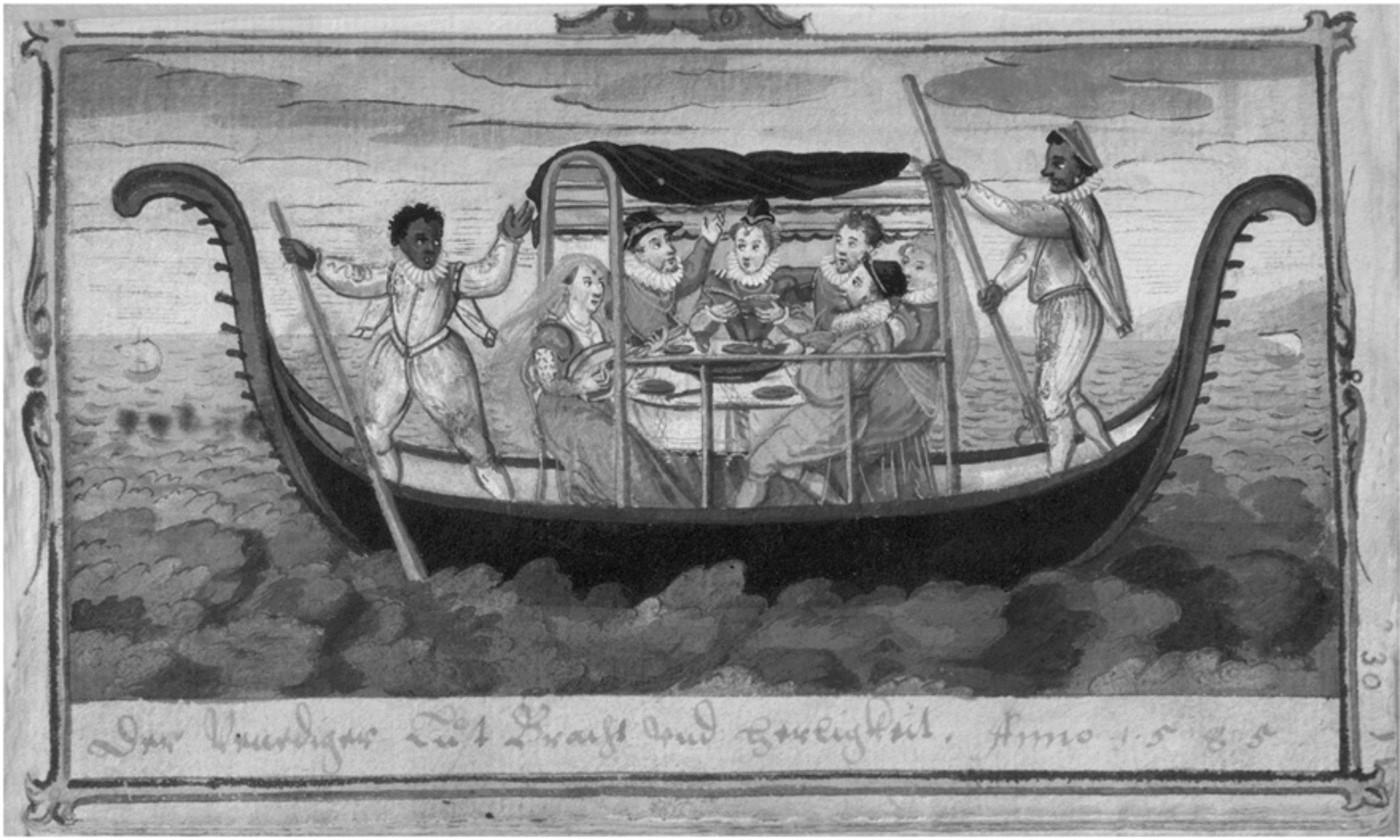

gondolas in Venice, but also outside the city, portraying several hunters on small boats being rowed by Moors (1490-1495). German painter David Brentel, who visited

Venice circa 1585 and either painted or bought the painting he entitled, "The Venetian Love of Display and Magnificence," depicted

two Moors rowing a larger, covered gondola with 6 people around a table.

By the mid 1500s, Lisbon and other cities in Portugal had high numbers of Moorish gondoliers and boatmen, many of whom hailed from West Africa

Indeed, Alvise Ca' da Mosto (1432-1488), a Venetian explorer who traveled to the Senegambia region of West Africa, remarked on the

locals' exceptional skills at rowing and swimming. In the aforementioned "Chafariz d'el rei" piainting, moorish ferrymen are depicted

in a rowboat in Lisbon's busy Alfama Harbor circa 1560-80.

A dinner party aboard a Venetian gondola steered by two Moors in Venice (c. 1585)

|

A Moorish gondolier helps ferry 2 aristocrats in Italy, in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (c. 1595)

|

A Moorish ferryman and his passenger in Lisbon's busy Alfama Harbor (c. 1560-1580)

|

Continue >>