|

Pre-Maritime Aquatic Civilization

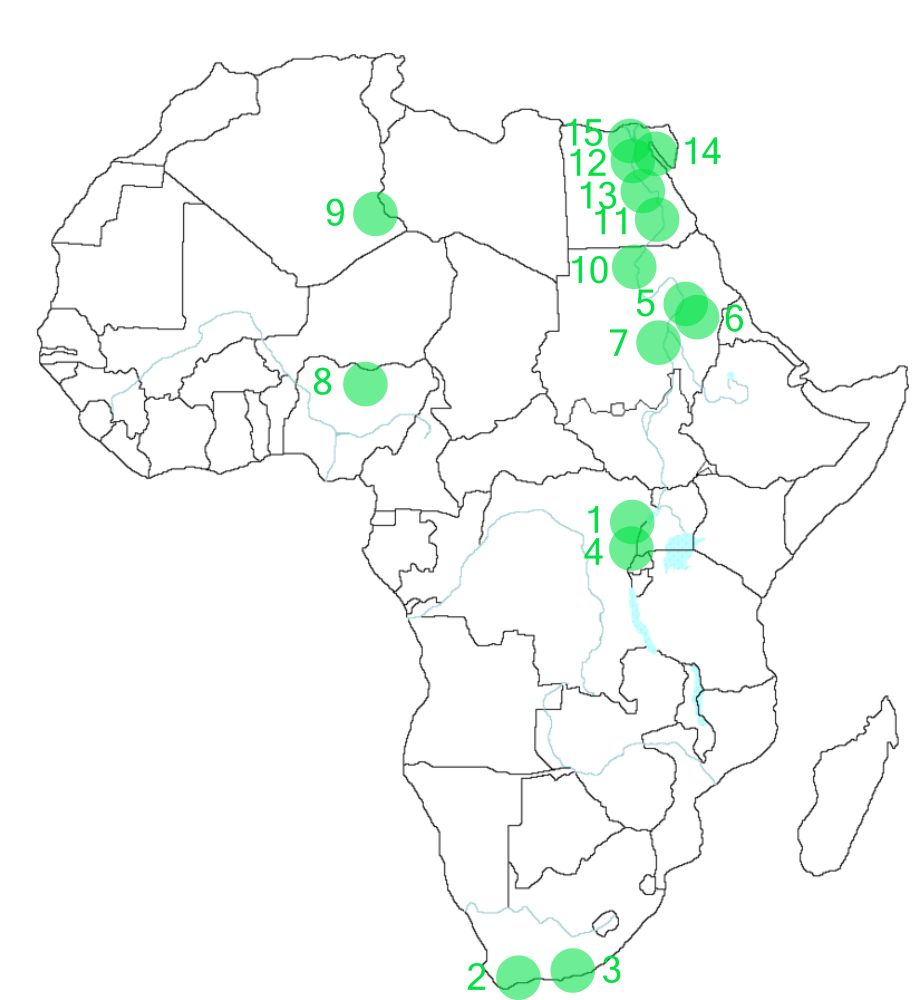

Pre-maritime civilization developed from early humans' consumption of fish, a practice continued from early hominids in East Central Africa. Numerous early hominid sites near large bodies of water (e.g., Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, East and West Turkana in Kenya, and Senge in Democratic Republic of Congo) in Africa have fish remains that could suggest fishing occurred 2-1 million years ago. However, the absence of tools at such sites suggests the fish could have been scavenged as opposed to being caught, which requires cognitive skills that many researchers believe developed much later in history. Early modern humans in Central Africa, however, appear to have been the first to construct harpoons and other tools that provide strong evidence they were fishing nearly 90,000 years ago.

The world's oldest harpoon, the so-called Semliki or Katanda Harpoon, was discovered along with catfish bones in 1988 on Democratic Republic of Congo's Semliki River in the Nile River Valley. First dated to 88,000 BC, the global archaeological community was initially skeptical that humans possessed such advanced technology at that period of time, but the artefact's authenticity was bolstered by the discovery of other harpoons and artefacts of similar age near the site.

Further evidence that humans continuously fished millennia later can be found at other sites across Africa. For instance, at the Blombos Cave (70,000 BC) and Klasies River (60,000 BC) sites in South Africa, the presence of large quantities of ancient fish bones from a few species suggests they were caught rather than scavenged along the shore. Although archaeologists had studied the fish remains at these two sites since the 1970s, more recent and thorough analyses made by University of Cape Town researchers concluded that much of the fish had been caught.

At Lake Edward in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Ishango site hosts numerous ancient artefacts, including sophisticated harpoons dating to 25,000 BC along with the tools used to create them.

|

|

Oldest Evidence of Boating

More than 10,000 years ago, Africans began venturing out on rafts or constructed boats in order to continue catching and perhaps trading fish that did not come close enough to the shore to catch. Archaeozoological work at sites along the Atbara River (a Nile River tributary in Central Sudan) revealed evidence that suggests the early use of boats for fishing. At the El Damer (8050-7800 BC) and Aneibis (7900-7600 BC) sites, evidence of the large-scale consumption of fish that do not typically come ashore suggests the use of fishing boats. Combined with the development of large-scale agriculture on the banks of the Nile and later on the Niger River, ships became the primary mode of trade and transportation.

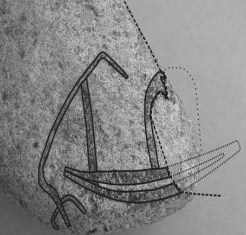

Oldest Depiction of a Boat

Evidence of the use of large ships can be found at the El Salha Archaeological Project, located to the west of Khartoum in Central Sudan (at the confluence of the Blue and White Niles), where the image of a vessel is etched on a broken granite pebble dating between 7050 and 6820 BC (Khartoum Mesolithic Group). The boat's domed enclosure and large rear oar (or anchor) are typical of other Pre-dynastic depictions of ships found in Sudan and Egypt.

|

|

|

The oldest actual boat ever discovered in Africa, the so-called Dufuna Canoe, dates to 6500 BC, making it the world's second oldest known vessel. The canoe was partially discovered by a Fulani cattle herdsman digging a well near Dufuna, Nigeria not far from the Komadugu Gana River (i.e., in the Lake Mega Chad region, which researchers believe was a sea that existed before the smaller, current Lake Chad in Central Africa). Measuring 27.6 feet long, the Dufuna Canoe attests to ancient Africans' use of advanced technology and possibly maritime trade. It is nearly 3 times the length of and carved in a more sophisticated manner than the so-called Pesse canoe, which was found in the Netherlands and believed to be the only boat older than the Dufuna canoe.

Early Depictions of Boats and Large Ships

|

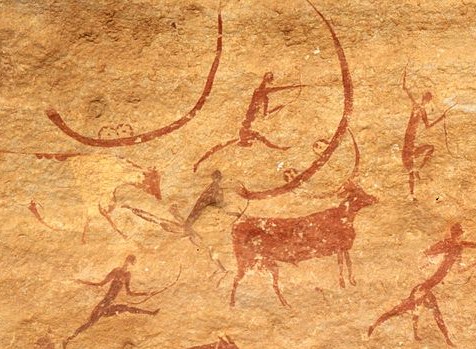

Dozens of petroglyphs that depict more elaborate large ships with tall sailing masts, large oars, covered superstructures and chairs have been found in central Sudan at Sabu Jaddi (4500 BC) and Egypt's Central Eastern Desert at Wadis Abu Subeira, Abu Wasil, Baramiya, Gharb Aswan, Hajalij, Hammamat, Kanais, Mineh, Nag el-Hamdulab, Qash, and Salam (early Naqada I period, 4400-3500 BC). Pottery and linen with representations of ships bearing large sails and multiple oars also appeared during the so-called "Naqada II Period" (3600 - 3250 BC).

|

|

Ships as Early Cultural Symbols

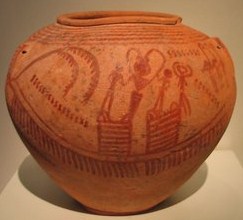

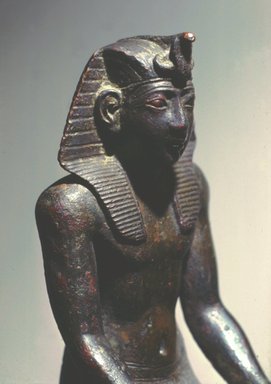

Models of boats were buried in predynastic tombs at Hu and Gebelein in Southern Egypt, a cultural practice that continued for thousands of years as a testament to the importance of the boat in everyday life. While some models and paintings of boats clearly represented actual ones used for fishing, sporting or for ceremonial purposes, others were apparently symbolic representations of the solar barque called "Atet", which ferried the Nilotic solar deity Ra through the sky over the 12 hours of the day. Ra also took the form of the rising sun deity Khepri and was often depicted as a scarab accompanied by two people on a boat. This depiction closely resembles older representations on predynastic pottery, such as the one shown below from the Naqada II Period, featuring a human figure with arms raised next to two others on a ship.

|

|

|

|

Archaeologists have uncovered 14 wooden vessels measuring as much as 75 feet long and 10 feet wide that were buried about 5,000 years ago in long brick enclosures near Abydos. While the ships are located at the tomb of Khasekhemwy (2nd Dynasty, 2675 BC), they were likely buried many years earlier during the reign of Aha (1st Dynasty, 2920-2770), making them the world's oldest wooden boats that are not dugout canoes (such as the 8,500-year-old Dufuna canoe found in Nigeria). Other wooden ships of the same era were found buried at tombs near Saqqara and Menefer. But the remains of the largest ancient seafaring vessel ever discovered was buried next to Khufu's (4th Dynasty, 2586-2566 BC) "Great Pyramid" at Giza. Generally believed to be mere funerary symbols like some model boats, as mentioned above, some scholars agree that such ships were used for various practical purposes, including making actual pilgrimages and for holding ceremonies, as further explained below. Indeed, archaeologists successfully reassembled the 1,224 timber pieces of Khufu's ship (shown at right), which measures 143 ft (44 m) by 19.5 ft (6 m), or more than twice as long as Christopher Columbus' longest vessel.

|

|

World's Oldest Ports

Not far from Khufu's ship, archaeologists uncovered the ruins of an extensive port dating to at least 2500 BC. Moreover, the evidence of juniper, pine and oak trees, which are not native to Egypt, confirms trade with regions of the Levant and Western Asia. At Wadi al-Jarf on the Red Sea, archaeologists also discovered evidence of a port that dates to the same era. There are numerous ancient docks, or galleries carved into stone, that contain ropes, anchors covered with writing, pieces of ship sails and oars, food storage jars, and the world's oldest known papyrus documents. And farther south at Wadi Gawasis, archaeologists discovered an ancient port with Dynastic stelae dating as far back as the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1802 BC), docks, ship timbers, ropes, anchors and in-tact oars, and pottery (1400-1500 BC). It is worth noting that this port is near the closest point on the Red Sea to the ancient capital city of Waset (Thebes).

Oldest Documented International Maritime Trade

|

Sahure (5th Dynasty, 2487-2475 BC) also documented his trade missions with the Levant. Inscriptions in his pyramid at Abusir show sailors raising a tall mast on a large sailing ship, as well as large shipments of timber, jugs and even brown bears, which are not native to Africa. Archaeologists even found an ancient axe head attributed to Sahure's sailing crew that docked at the coastal Lebanese city of Nahr Ibrahim.

|

Oldest Intracontinental Maritime Trade

As imports of foreign goods like timber expanded, the trade of Nile Valley staples such as wheat, papyrus, wine, frankincense, domesticated and wild animals, textiles, furniture, and precious metals flourished. Scenes on the walls of the tomb of Khaemwaset, west of Waset (1500 BC), show grape cultivation, winemaking, bottling and transporting via ships. At Hatshepsut's temple at Deir el-Bahri (1450 BC), scenes depict the exporting of boswellia (frankincense) trees from Punt (South Sudan) At the nearby tomb of Unsu (1450 BC), there are detailed depictions of farmers seeding and tilling the soil, and harvesting and loading grain onto ships. In the same region, at the tomb of Amenhotep Huy (1400 BC), large groups of people are seen shipping gold, furniture, shields made of animal skin, cattle, giraffes and what appear to be horses or donkeys on well decorated ships.

|

|

|

|

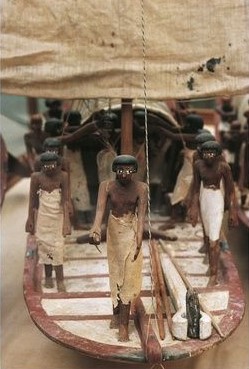

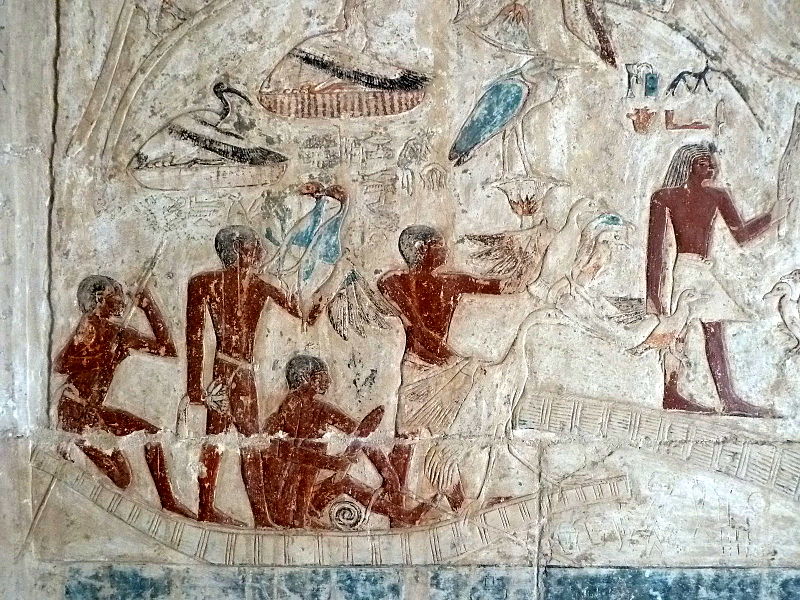

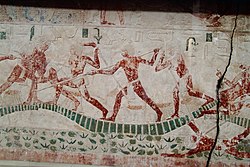

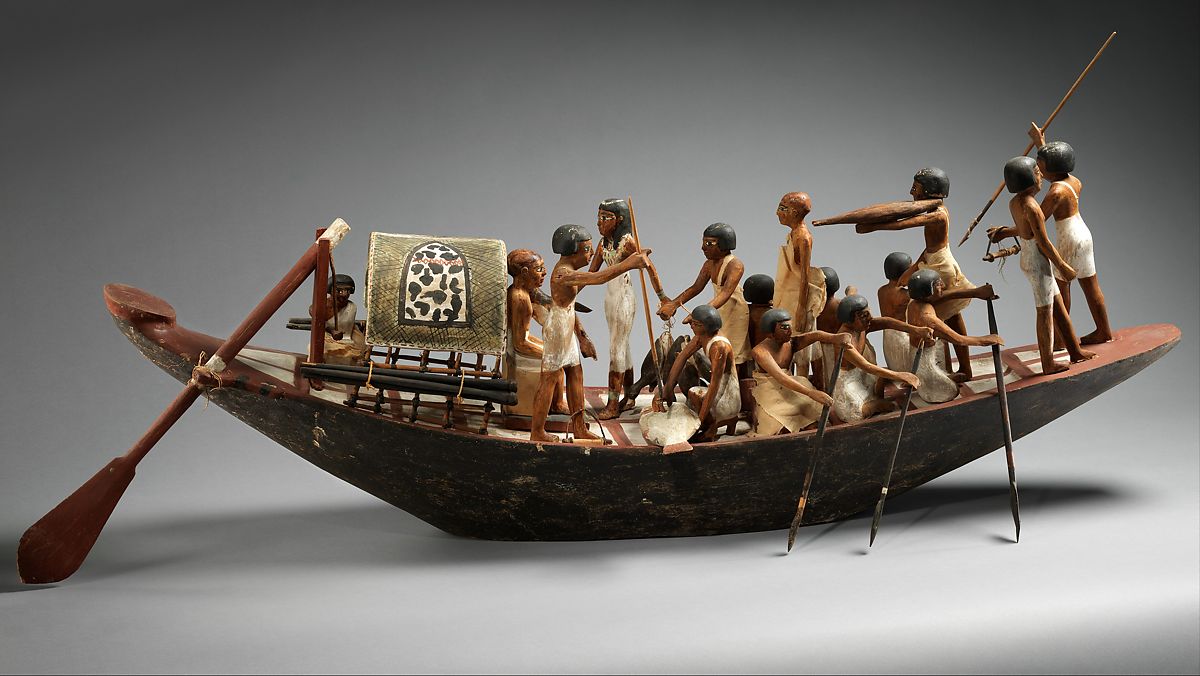

Boats were not only used for major commercial trading but for various practical uses in everyday life. Fifth Dynasty paintings from an unknown tomb at Saqqara, show men standing on small reed boats participating in a fighting sport involving small balls and spears. Nearby, at the mastaba of Nikauisesi near Saqqara (2500 BC) show organized trips on reed boats to hunt fowl and fish. Such elaborate hunting scenes became common in tombs in Saqqara and were portayed in a similar manner in tombs elsewhere, especially at the so-called Theban necropolis centuries later. Famous examples are seen on the walls of the tomb of Nebamun near Waset (1350 BC) and the tomb of Menna. Other high officials created model boats (in addition to models of other scenes) portraying fishing and hunting expeditions, such as the one found in Meketre's tomb near Waset (1981-1975 BC). This depiction better demonstrates how nobles lived, with Meketre, who served under Mentuhotep II (2010-1998 BC), and his son riding in a covered part of the ship while others row the oars and catch fish and fowl.

|

|

|

|

Ceremonial Uses

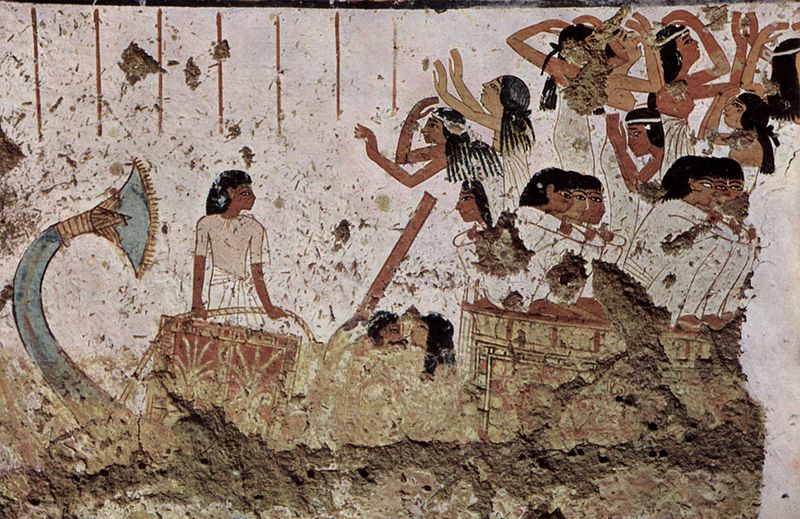

As aforementioned, ships were often used for ceremonial purposes. A model from Meketre's tomb shows a pilgrimmage to the predynastic capital of Abydos, the original mecca where the tomb of Asar (Osiris) is located. Noticeable differences in this ship versus those merely used for sporting or fishing/hunting are that the ship used for pilgrimmages is larger, decorated and features a tall sailing mast, obviously used for faster travel over longer distances and to travel south against the Nile's current. Such ships also served as ancient limousines and hearses for the oldest documented funeral processions. Particularly in the era of the so-called New Kingdom, elaborate scenes of riparian funeral processions became common in tombs of nobles througout the Theban necropolis. For example, the tombs of Nebamun (1350-1300 BC) and Kyky (1292-1189 BC) feature numerous, well appointed ships carrying people, including professional wailers, and one larger ship carrying the sarcophogus.

|

|

|

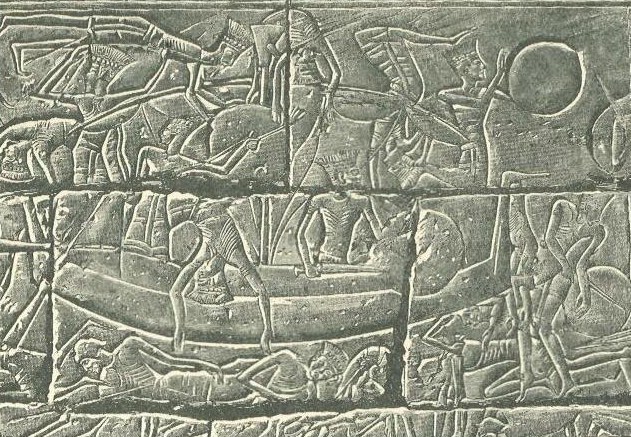

Nilotic people also documented their use of ships in battle. In fact, the world's oldest known representation of what could be considered naval warfare was carved on a knife found at Gebel El-Arak near Abydos (3300-3200 BC). The object features hand-to-hand combat above several ships, suggesting a representation of a naval battle. However the style of the engravings and the inclusion of a bearded figure, with a hat on the reverse seem more similar to ancient artifacts found in Iraq, specifically from Ur. Perhaps this was an imported piece or simply styled after such artifacts from Ur. More detailed documentation of early naval warfare, however, can be found at the tomb of Ahmose, Son of Ebana at El Kab (17-18th Dynasty, 1560-1520 BC), who describes leading the navy on ships to defeat the foreign Hyksos at their capital of Avaris in the Nile Delta. And at the tomb of Ramesses III (20th Dynasty, 1186-1155 BC) at Medinet Habu near Waset, the written description of the Battle of Djahy is the longest Medu Neter (hieroglyphic) inscription ever found. It details Ramesses III defeating the so-called "Sea People" (a broad term used to refer to the 7 groups of people named in the inscription: Denyen, Peleset, Shekelesh, Sherden, Teresh, Tjekker, Weshesh) on ships.

|

The longest known voyage, and the world's first to circumnavigate Africa, was taken by Necho II (26th Dynasty, 610-595 BC). According to early Greek historian Herodotus (Histories 4.42), Necho II sent a fleet of ships from a port on the Red Sea, south around the continent of Africa, to the Nile. Herodotus also reported that unlike in the northern hemisphere, the sun rose and set in a different part of the sky as the sailers sailed around southern Africa, lending credence to Herodotus's account.

Rise of Coastal Trade Cities and Oldest Documented Tariffs

The increased use of large ships and the growth of Mediterranean trade fueled the rise of a deep water sea ports along the coasts of Africa. Despite common misconceptions that Alexander of Macedonia was the first to found a city on the Mediterranean coast of Africa in 331 BC, evidence of human occupation and metallurgical industrial activity at Rhakotis dates to as early as 2686 BC, making it one of the oldest known coastal cities in the world, as further discussed below.

Thonis

Farther northeast, where the Nile meets the Mediterranean, lies the ruins of the pre-Alexandria city of Thonis or Heracleion, as it was called by Greek writers. Underwater archaeologists have located the submerged remnants of this canaled city dating as far back as the so-called Late Period (664-332 BC), including stone temples dedicated to Khonsu, Tehuti (Toth), Asar (Osiris) and Amun-Gereb, as well as statues, statuettes, crowns, jewelry, vases, amulets, and historical documents such as the Thonis stela. Also known as the decree of Nectanebo I (c. 380-360 BC), the Thonis stela describes a maritime import tax on ships sailing into the harbor (i.e. customs duties), which would be paid to the local temple. This and a similar version, called the Naukratis stela (which was found in 1899), represent the oldest documented evidence of international maritime tariffs.

|

|

|

Rhakotis or Alexandria

Greek colonizers later steered international trade towards the ancient Kemetic or Egyptian city of Rhakotis, where Alexander of Macedonia commissioned the construction of a new city. Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), a Roman author and naval commander, described Alexandria as being built on top of the older city of Rhakotis. In his Natural History, Pliny says that Alexander built Alexandria on "the spot having previously borne the name of Rhacotes."

Greek historian and geographer, Strabo (c. 63 BC) also confirmed that Rhakotis predated Alexandria. In his Geography, Strabo described Rhakotis as a military station that Kemetic or Egyptian kings used to guard against foreign invaders from the north:

|

Adulis

Along the Red Sea lies the ruins of Adulis (near modern day Zula, Eritrea), which archaeological evidence and historical texts suggest was a powerful Red Sea trading hub. Archaeologists have identified 8 types of amphora ceramics dating from as far back as 1000s BC to 700 AD, that were imported from inland Eritrea/Ethiopia, Egypt, Greece, Tunisia and Rome--a testament to the ancient port's international trade networks. Archaeologists working in Egypt's Red Sea ports of Myos Hermos and Berinike also identified pottery that they attribute to Adulis. The first known mention of Adulus in literature was by Roman historian Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 AD) who described the city as the "principal mart for the Troglodytae and the people of Aethiopia." Adulis was also described in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c. 50-60 AD) by an anonymous Roman Egyptian who logged accounts of trading voyages around the Red Sea and Indian Ocean:

During his travels to Adulis, a Greek traveling monk, Cosmas Indicopleustes (c. 500s AD), copied an inscription describing an anonymous Aksumite king's military campaigns in Africa and the Arabian peninsula (c. 200s AD) that expanded the Axumite empire:

|